Low back pain – What next?

Posted on 08th April 2025 by Paul FrankhamWhy does my lower back hurt?

You are not alone! In fact 80% of individuals will experience an episode of low back pain in their lifetime (Alotabib et al., 2024). Low back pain is a multifactorial condition with many possible sets of causes, risk factors and links to other preexisting conditions. The main predictors of low back pain include physical stress, for instance, heavy lifting, repetitive movements or awkward postures, but equally sedentary lifestyle, poor fitness, and strength can make an individual at greater risk of developing back pain. Various factors related to emotional and psychological status (e.g., anxiety, depression, coping strategies) can modify the severity and chronicity of low back pain that you experience (Wong, Karppinnen, Samartzis, 2017).

What causes lower back pain?

LBP symptoms can derive from ‘many potential anatomic sources, such as nerve roots, muscle, fascial structures, bones, joints and intervertebral discs’ (Mattiuzzi, Lippi and Bovo, 2020). Furthermore, in some instances the presentation of low back pain may also be generated from other surrounding joints such as the pelvis and hip that refer symptoms to the low back area. The diagnostic evaluation of LBP can be challenging, and only 15% of all instances of low back pain show a specific patho-anatomical relationship between the pain and one or more pathological processes (Casser, Seddigh and Raschumann 2016). Therefore, pragmatically, low back pain is often characterised in practice as ‘specific’ or ‘non-specific’ (Almedia and Kraychete, 2017). For many LBP cases there is often a multi-dimensionality to the pain experience that can be biologically (medically), psychologically (cognition and emotions) and socially driven with common symptoms such as loss of mobility and restriction of function, abnormal perception and mood and pain-related behavior, disturbances of social interaction and occupational difficulties encompassing all three domains (Casser, Seddigh and Raschumann 2016).

Is my back pain serious?

While the back pain you experience may be very uncomfortable and significant, it is very rare for low back pain to be driven by underlying serious pathology termed ‘Red Flags’; these include cancers, infections or tumours. You should be reassured that a small number, only 2% of all low back cases, have this presentation (Petty, 2024). Episodes of acute LBP usually have a good prognosis, with rapid improvement within the first 6 weeks. (Almeida et al, 2018).

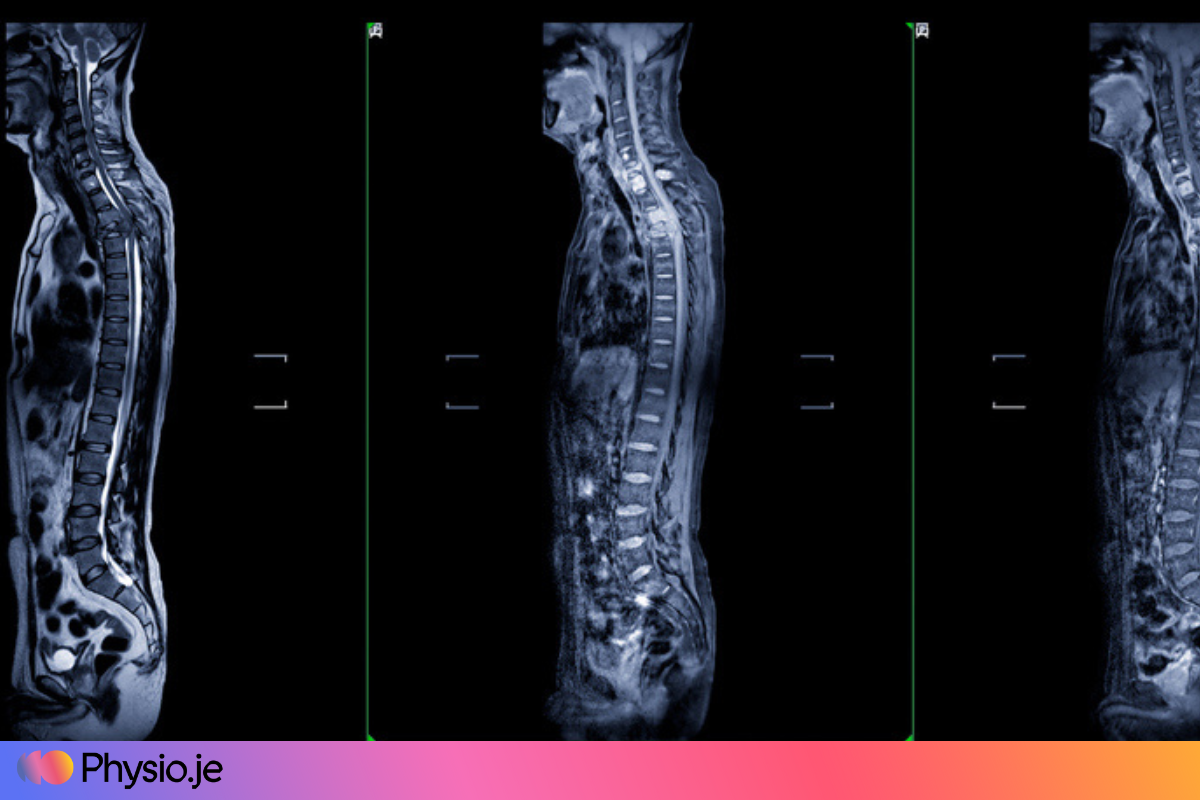

Do I need imaging?

No not necessarily. Current guidelines like the American College of Radiology recommend against imaging for LBP within the first 6 weeks unless red flags are present (Allegri et al. 2016). There is growing evidence that Imaging findings are weakly related to symptoms. One clinical study reviewing current trends and practice in lumbar spine imaging to help influence practice recommendations found that MRI changes did not necessarily correlate with symptoms when exploring an asymptomatic cohort aged 60 years or older, 36% had a herniated disc, 21% had spinal stenosis, and more than 90% showed visible degenerative spinal changes on the scan (Chou, Deyo and Jarvik 2015). Resultantly it is unclear whether “abnormal” MRI findings reflect pain generation and the experience of back pain or whether they are normal structural variants unrelated to the pain experience.

Current Guidelines for low back pain

Extended rest is generally discouraged and is thought to adversely affect recovery. Instead, short 5–10-minute rests are advised. Small regular activity is preferable to less frequent and long activity with physical activity within tolerable levels considered to be a key component of self-management and many guidelines’ recommendations. The NICE guidelines, a clinical excellence body in the UK, recommend that individuals with low back pain remain active, resuming normal activities that are tolerable as soon as possible. Central to their recommendations is referral to physiotherapy (NICE, 2016).

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy found Grade A evidence (Extremely High) supporting exercise training interventions, specifically stability exercises that aim to restore normal movement patterns in the management of acute and persistent low back pain. Moreover, Grade A evidence was found for manual therapy that involved joint mobilization procedures to improve spine and hip mobility and for pain education and reassurance. Physiotherapists have a wide remit of these skills and therefore are well placed to deliver effective interventions to address low back issues (George et al. 2021).

Practical steps to manage my low back pain

When first experiencing your low back pain, it is important to identify the aggravating factors and activities quickly. Once you have a grasp of these, you can then modify your activity accordingly to reduce the amount of time spent in these positions. For example, if your pain is aggravated from prolonged seating then you should try to ensure you get up at regular intervals. Conversely, if your pain is aggravated from forward bending movement, then initially, you should try to minimise the time spent performing activities such as hoovering and washing, which involve repetitive lumbar flexion. During the early stages of low back pain, pain relief such as paracetamol and anti-inflammatories are also advisable alongside the application of hot and cold modalities in helping dampen your pain. If you do find your pain is severe and is causing difficulty in completing very basic daily tasks such as washing and dressing, then it may be advisable to contact your GP to seek a pain review for prescribed medication that can help bring your pain under better control. If possible, you should try to continue with as much of your normal activity as possible. Gym training should be continued if tolerable; reducing weights by 50% is a good starting point. If unable to continue with certain activities due to the pain, then it would be advisable to find more comfortable alternatives. For example, cycling or rowing may be considered if pain is aggravated by running and walking (more extension-based activity) and vice versa. Pool-based exercise can also be brilliant at this time due to the extra buoyancy it provides. Trying some of these suggested actions would be a good place to start whilst looking to get physiotherapy help for specific remedial treatment and for strengthening exercises.

Where to start with exercises?

Gentle range of movement and strengthening exercises should be started as soon as possible after an episode of acute back pain begins. Starting with gentle movement in a comfortable range and ensuring pain remains tolerable throughout performance.

LBP is often associated with altered muscle function, including delayed activation, abnormal recruitment patterns, and endurance limitations (Tikhile and Patil, 2024). The pain can reinforce certain movement patterns and behaviors which can result in increased muscle tension and guarding.

Deep breathing can be an excellent way to downregulate some tension. Aim to take 10 deep breaths before performing each of these exercises.